Creating Rubrics for Effective Assessment Management

How this will help

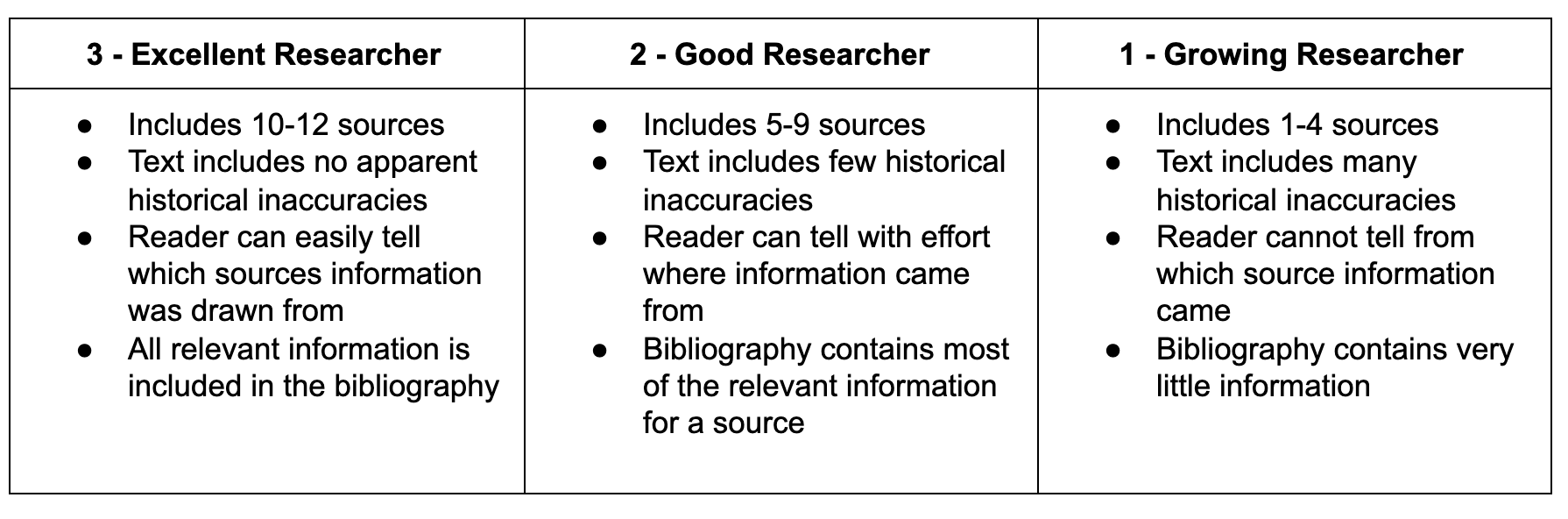

Regardless of whether your course is online or face to face, you will need to provide feedback to your students on their strengths and areas for growth. Rubrics are one way to simplify the process of providing feedback and consistent grades to your students.

What Are Rubrics?

Rubrics are “scoring sheets” for learning tasks. There are multiple flavors of rubrics, but they all articulate two key variables for scoring how successful the learner has been in completing a specific task: the criteria for evaluation and the levels of performance. While you may have used rubrics in your face-to-face class, rubrics become essential when teaching online. Rubrics will not only save you time (a lot of time) when grading assignments, but they also help clarify expectations about how you are assessing students and why they received a particular grade. It also makes grading feel more objective to students (“I see what I did wrong here”), rather than subjective (“The teacher doesn’t like me and that’s why I got this grade.”).

When designing a rubric, ideally, the criteria for evaluation need to be aligned with the learning objectives [link to learning objectives] of the task. For example, if an instructor asks their learners to create an annotated bibliography for a research assignment, we can imagine that the instructor wants to give the students practice with identifying valid sources on their research topic, citing sources correctly (using the appropriate format), and summarizing sources appropriately. The criteria for evaluation in a rubric for that task might be

- Quality of sources

- Accuracy of citation format for each source type

- Coherence of summaries

- Accuracy of summaries

The levels of performance don’t necessarily have a scale they must align with. Some rubric types might use a typical letter grading scale for their levels – these rubrics often include language like “An A-level response will….” Other rubric types have very few levels of performance; sometimes they are as simple as a binary scale – complete or incomplete (a checklist is an example of this kind of rubric). How an instructor thinks about the levels of performance in a rubric is going to depend on a number of factors, including their own personal preferences and approaches to evaluating student work, and on how the task is being used in the learning experience. If a task is not going to contribute to the final grade for the course, it might not be necessary (or make sense) to provide many fine-grained levels of performance. On the other hand, an assignment that is designed to provide detailed information to the instructor as to how proficient each student is at a set of skills might need many, highly specific levels of performance. At the end of this module, we provide examples of different types of rubrics and structures for levels of performance.

Meet Your Teaching Goals

In an online course, clear communication from the instructor about their expectations is critical for student success and success of the course. Effective feedback, where it is clear to the learner what they have already mastered and where there are gaps in the learners knowledge or skills, is necessary for deep learning. Rubrics help an instructor clearly explain their expectations to the class as a whole while also making it easier to give individual students specific feedback on their learning.

Although one of the practical advantages to using rubrics is to make grading of submitted assignments more efficient, they can be used for many, not mutually exclusive, purposes:

- Highlighting growth of a students’ skills or knowledge over time

- Articulating to learners the important features of a high-quality submission

- Assessing student participation in discussion forums

- Guiding student self-assessments

- Guiding student peer-reviews

- Providing feedback on ungraded or practice assignments to help students identify where they need to focus their learning efforts.

Examples of Different Rubrics

Different styles of rubrics are better fits for different task-types and for fulfilling the different teaching aims of a rubric . Here we focus on four different styles with varying levels of complexity: single point rubric, Specific task rubrics, general rubrics, holistic rubrics and analytical rubrics (Arter, J. A., & Chappuis, J., 2007).

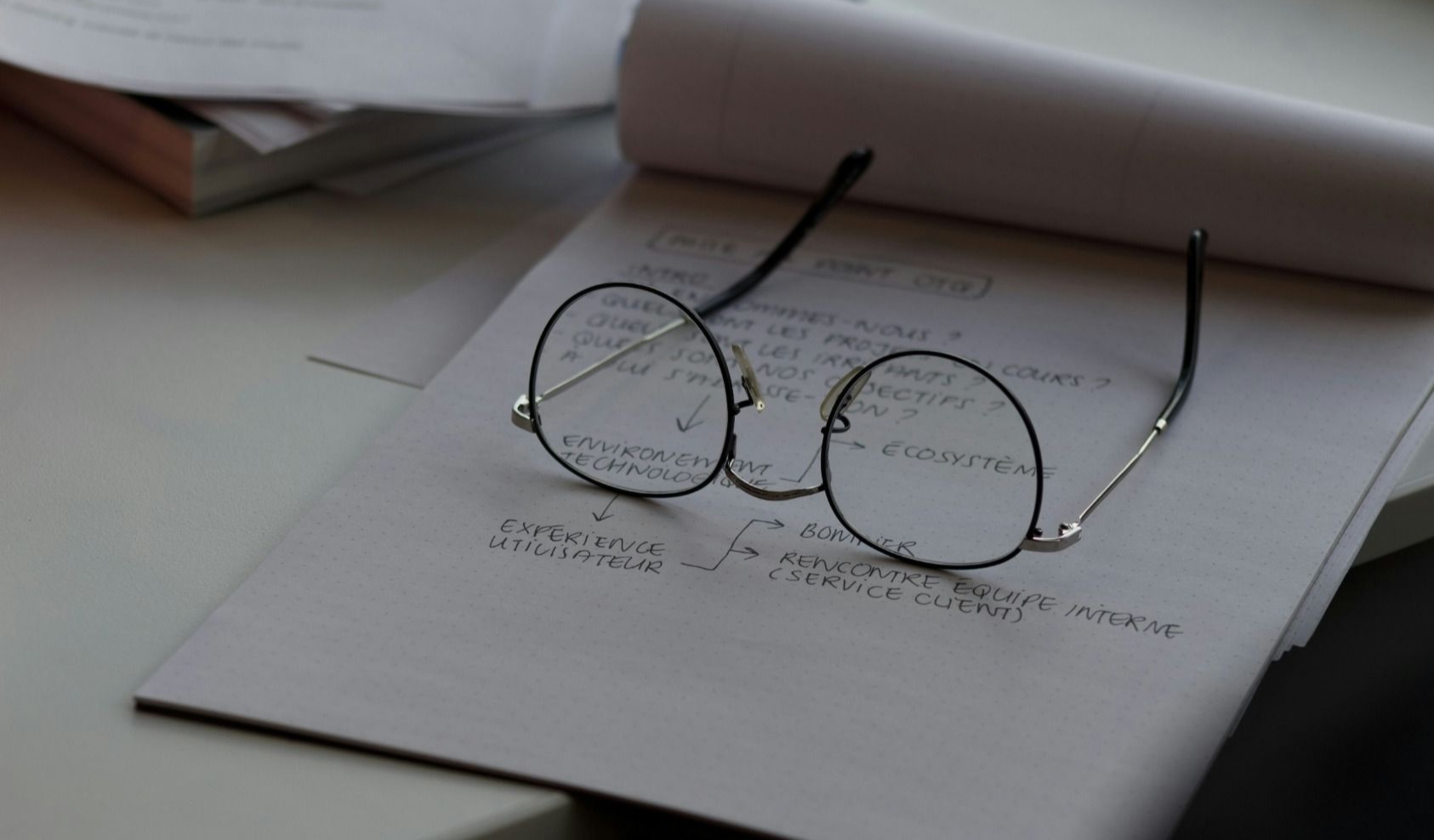

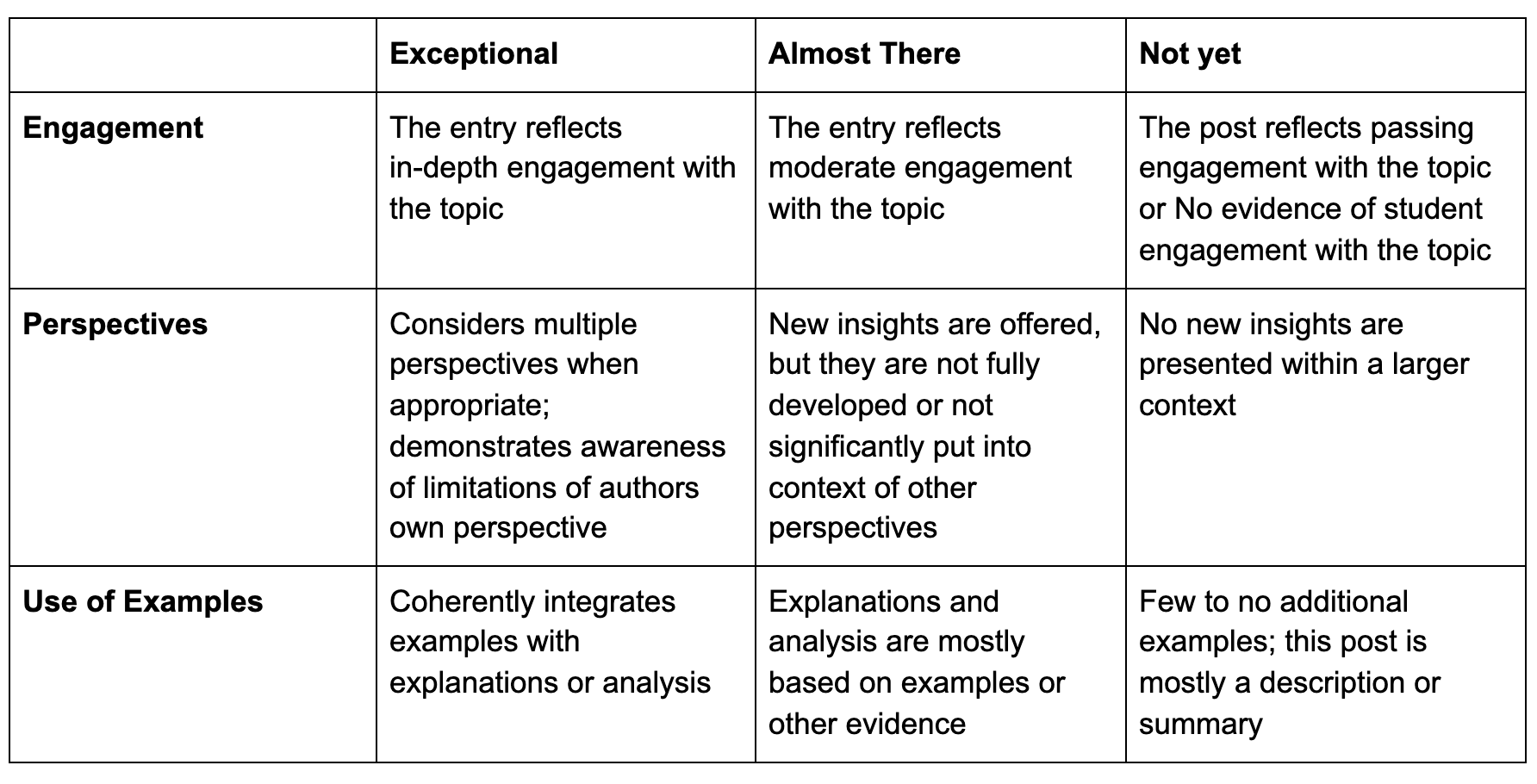

Single-Point Rubric

Sometimes, simple is easiest. A single-point rubric can tell students whether they met the expectations of the criteria or not. We’d generally recommend not using too many criteria with single-point rubrics, they aren’t meant for complicated evaluation. They are great for short assignments like discussion posts.

Example task: Write a 250 discussion post reflecting on the purpose of this week’s readings. (20 points)

Example rubric:

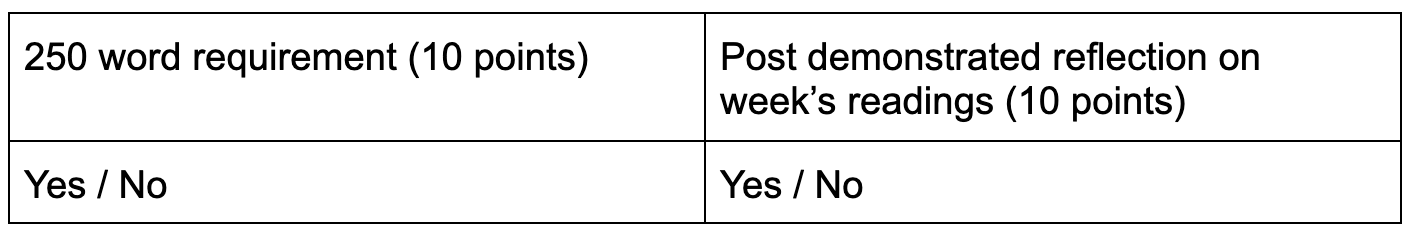

Specific-Task Rubric

This style of rubric is useful for articulating the knowledge and skill objectives (and their respective levels) of a specific assignment.

Example task:

Design and build a trebuchet that is adjustable to launch a

- 5g weight a distance of 0.5m

- 7g weight a distance of 0.5m

- 10g weight a distance of 0.75m

Example rubric:

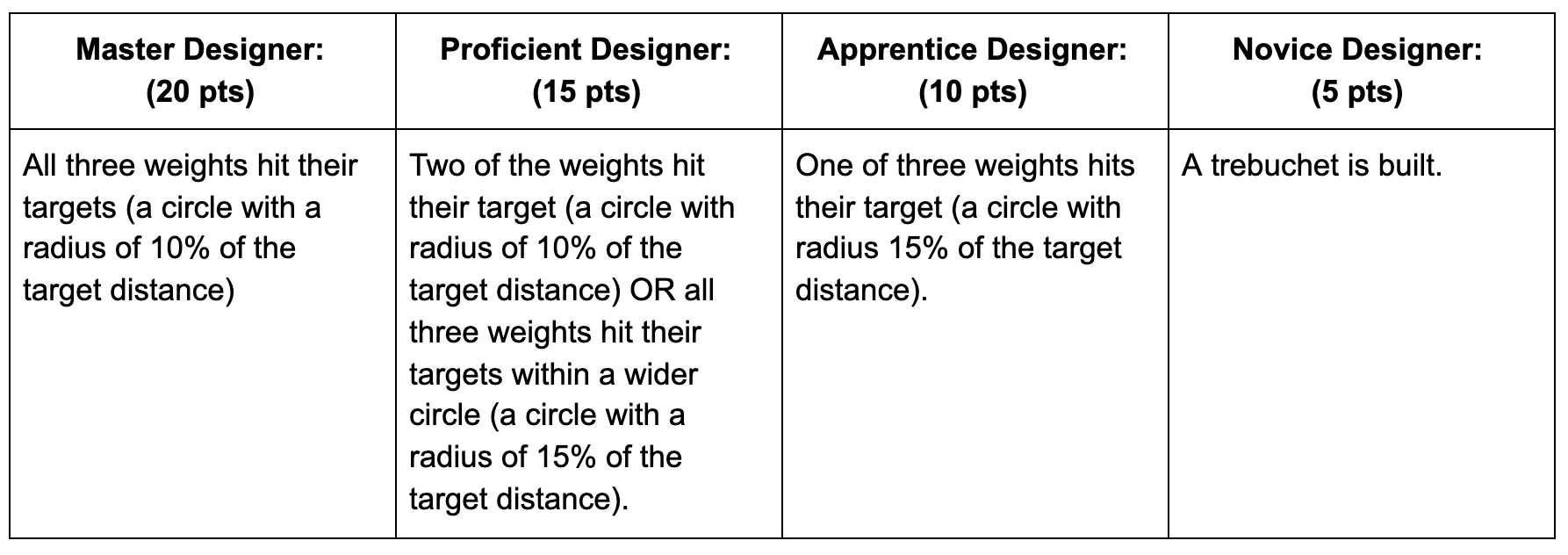

Holistic Rubric

This style of rubric enables a single, overall assessment/evaluation of a learner’s performance on a task

Example task:

Write a historical research paper discussing ….

Example rubric:

General Rubric

This style of rubric can be used for multiple, similar assignments to show growth (achieved and opportunities) over time.

Example task:

Write a blog post appropriate for a specific audience exploring the themes of the reading for this week.

Example rubric:

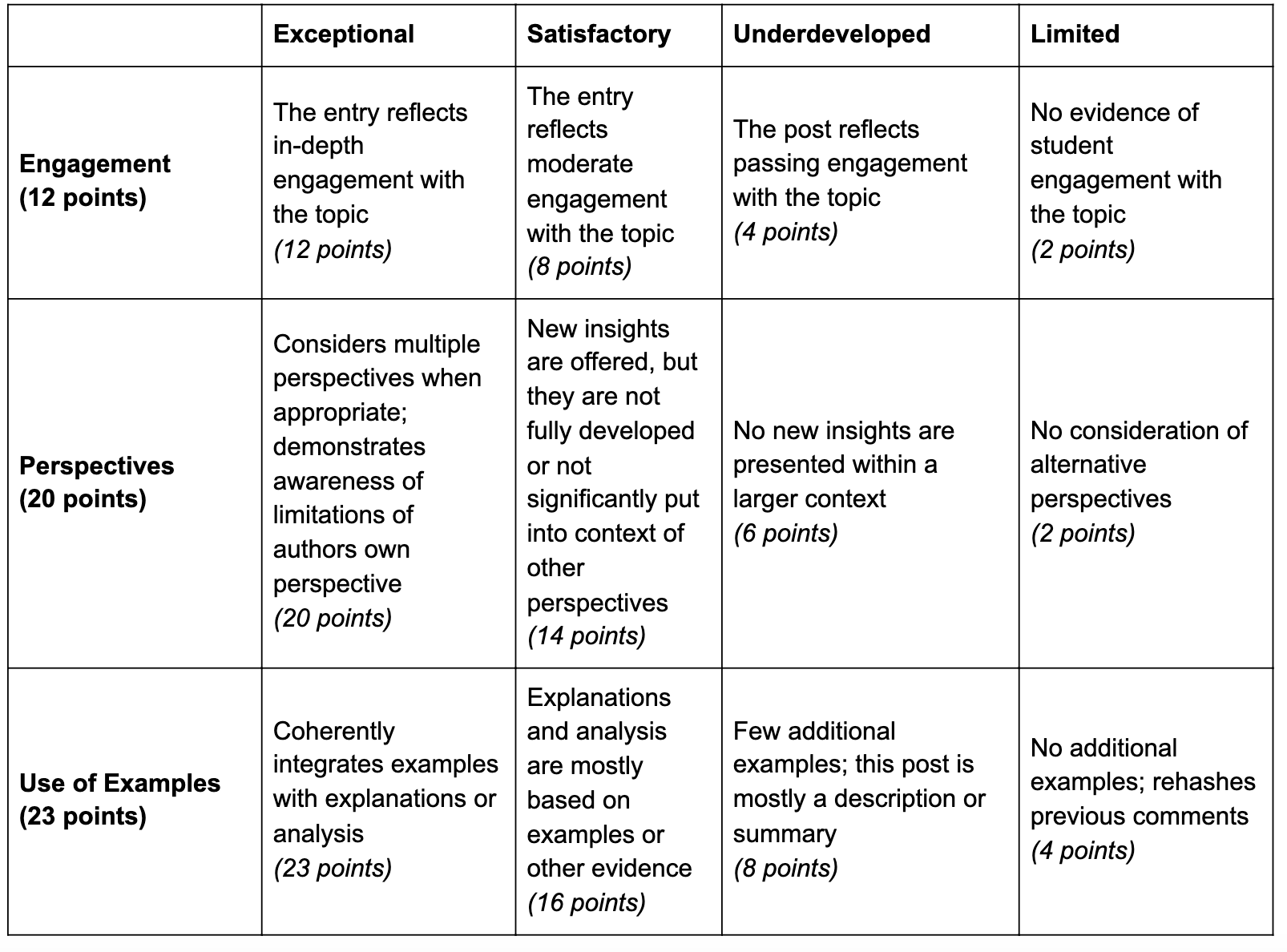

Analytic Rubric

This style of rubric is well suited to breaking apart a complex task into component skills and allows for evaluation of those components. It can also help determine the grade for the whole assignment based on performance on the component skills. This style of rubric can look similar to a general rubric but includes detailed grading information.

Example task:

Write a blog post appropriate for a specific audience exploring the themes of the reading for this week.

Example rubric:

Designing Your Own Rubric

You can approach designing a rubric from multiple angles. Here we outline just one possible procedure to get started. This approach assumes the learning task is graded, but it can be generalized for other structures for levels of performance.

- Start with the, “I know it when I see it,” principle. Most instructors have a sense of what makes a reasonable response to a task, even if they haven’t explicitly named those traits before. Write out as many traits of a “meets expectations” response as you can come up with – these will be your first draft of the criteria for learning.

- For each type of criterion, describe what an “A” response looks like. This will be your top level of performance.

- For complicated projects, consider moving systematically down each whole-grade level (B, C, D, F), describe, in terms parallel to how you described the best response, what student responses at that level often look like. Or, for more simple assignments, create very simple rubrics – either the criterion was achieved or not. Rubrics do not have to be complicated [link to single point rubric]!

- Share the rubric with a colleague to get feedback or “play test” the rubric using past student work if possible.

- After grading some student responses with it, you may be tempted to fine-tune some details. However, this is not recommended. For one, Canvas will not allow you to change a rubric once it has been used for grading. But it is also not recommended to change the metrics of grading after students have already been using a rubric to work from. If you find that your rubric is grading students too harshly on a particular criterion, Also, make sure you track what changes you want to make. You may want to adjust your future course rubrics or at least for the next iteration of the task or course.

Practical Tips

- Creating learning objectives for each task, as you design the task, helps to ensure there is alignment between your learning activities and assessments and your course level learning objectives. It also gives a head start for the design of the rubric.

- When creating a rubric, start with just a few levels of performance. It is easier to expand a rubric to include more specificity in the levels of performance than it is to shrink the number of levels. Smaller rubrics are much easier for the instructor to navigate to provide feedback.

- Using a rubric will (likely) not eliminate the need for qualitative feedback to each student, but keeping a document of commonly used responses to students that you can copy and paste from can make the feedback process even more efficient.

- Explicitly have students self-assess their task prior to submitting it. For example, when students submit a paper online, have them include a short (100 word or less) reflection on what they think they did well on the paper, and what they struggled with. That step seems obvious to experts (i.e. instructors) but isn’t obvious to all learners. If students make a habit of this, they will often end up with higher grades because they catch their mistakes before they submit their response(s).

- Canvas and other learning management systems (LMS) have tools that allow you to create point and click rubrics. You can choose to have the tools automatically enter grades into the LMS grade book.

- Rubrics can be used for students to self-evaluate their own performance or to provide feedback to peers.

Resources

University of Michigan

CRLT – Sample lab rubrics

Cult of Pedagogy – The single point rubric

Other Resources

The Chronicle of Higher Ed – A rubric for evaluating student blogs

Canvas – Creating a rubric in Canvas

Jon Mueller – Authentic assessment toolkit

Research

Arter, J. A., & Chappuis, J. (2007). Creating & recognizing quality rubrics. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Gilbert, P. K., & Dabbagh, N. (2004). How to structure online discussions for meaningful discourse: a case study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 36(1), 5–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2005.00434.x

Wyss, V. L., Freedman, D., & Siebert, C. J. (2014). The Development of a Discussion Rubric for Online Courses: Standardizing Expectations of Graduate Students in Online Scholarly Discussions. TechTrends, 58(2), 99–107. doi: 10.1007/s11528-014-0741-x